ARAN — From Workwear to High Fashion

Collection Aran - Studio Myr 2025

A Bit of History

In the windswept Atlantic, off the western coast of Ireland, lie the Aran Islands — Inis Mór, Inis Meáin, and Inis Oírr — rocky fragments of limestone and legend. For centuries, life here was shaped by the sea: the men went out to fish in their currachs, fragile tarred boats that braved the restless waves, while the women remained ashore, spinning, knitting, and mending. From this rhythm of labour and care emerged one of the most enduring garments of all time — the Aran sweater.

There is something deeply human about an Aran sweater. When you hold one in your hands, you feel more than the softness of the wool — you sense history, rhythm, and the life of an island people who, for generations, learned to live with wind, sea, and stone. Every stitch speaks of endurance, every pattern of belonging. It is clothing that carries memory in its very threads.

Its story is deeply woven into Ireland’s cultural identity, yet the roots of the Aran tradition reach further back and beyond its shores. The Aran is not an isolated invention, but the poetic culmination of centuries of northern European knitting culture — shaped by need, refined by skill, and transformed by imagination.

From Guernsey to Aran: Origins of an Icon

Long before the Aran patterns adorned the fishermen of the west, another maritime garment had already proven the power of knitwear — the Guernsey, or Gansey.

Fishermen form Guernsey wearing their traditional jumpers

Originating on the Channel Island of Guernsey as early as the sixteenth century, this practical woollen jumper was created for men who lived and worked at sea. Hand-knitted by women from tightly spun worsted wool, it was designed to resist wind and water, to dry quickly, and to last for years. Its construction was brilliantly functional: the front and back were identical, allowing the jumper to be reversed when one side began to show wear. A small diamond-shaped gusset under each arm offered ease of movement and reinforced the most stressed areas.

In these isolated coastal communities, knitting was both survival and expression. Each family created its own subtle variations of pattern — geometric ribs, ladders, and cables — motifs that could even identify a fisherman lost to the sea. The symbolism was humble but deeply human: rope-like cables spoke of safety and connection; diamond patterns suggested the nets and meshes of daily labour.

Gansey patterns

There are many Gansey patterns, often depicting fishing related iconography such as anchors, cables, and diamonds (nets) and some included weather and land influences, from lightning strikes and hail to furrows and the harvest. Many fishing and port towns around the North East coast had their own unique styles (which often came in handy when identifying drowned seamen). The most popular styles still available include Staithes, Runswick Bay, Whitby, Robin Hoods Bay, Scarborough, Filey, Flamborough, Patrington, and Humber Keel.

The meaning of the Guansey patterns

Filey: Known for intricate diamonds and cables, representing fishing nets and ropes.

Flamborough: Distinctive for its ‘Fence’ or ‘Flag’ pattern, symbolizing protection.

Staithes: This pattern from the village of Staithes is known for its unique combination of seed stitches and cables.

Scarborough: Recognizable by the ‘Marriage Lines’ or wavy lines that often represent the unpredictability of life and the sea.

Cornish: Originating from Cornwall, this pattern often features zig-zags and diamonds, symbolizing the ups and downs of the fishermen’s life.

Shetland: From the Shetland Isles, known for its Fair Isle motifs, a colorful and intricate design.

Norfolk: Characterized by a variety of geometric shapes and designs, reflecting the region’s maritime heritage.

Hebrides: From the Scottish Hebrides, this pattern often includes Celtic knots and twirls, linking to the rich Celtic culture.

Jersey: Named after the island of Jersey, this pattern can include diverse motifs, including stars and crosses, to represent the local culture and seafaring traditions.

Alderney: From the island of Alderney, often characterized by distinctive ribbing and textured stitches.

Isle of Man: Incorporates Manx Loaghtan wool and includes unique designs reflecting the Isle of Man’s Celtic and Norse heritage.

Robin Hood’s Bay: Characterized by sequences of ‘tree’ and ‘fern’ motifs. These motifs are typically surrounded by panels of simple seed stitches or moss stitches, creating a canvas where nature-inspired designs stand out.

Humber Keel: Named after the keelboats that once dominated the River Humber, this pattern celebrates the region’s maritime history. Key features include alternating bands of chevrons and cables. These chevrons, pointing upwards, are typically surrounded by ‘anchor’ motifs.

Seahouses: Hailing from the village of Seahouses in Northumberland, this design mirrors the bustling activity of this traditional fishing port.

In each of these patterns, while the designs and motifs might vary, a common thread is their embodiment of the region’s history, culture, and relationship with the sea. They stand as a testament to the craftsmanship and storytelling prowess of the communities that created them.

Two examples of original gansey’s

Technical knit and pattern information original gansey

Worsted Wool

Worsted is a high-quality type of wool yarn. It is named after the small English village of Worstead, in the county of Norfolk and this village was a center for manufacturing in the twelfth century.

During the Middle Ages, common agricultural practices were in flux because new breeds of sheep were being introduced in England. These sheep were raised in enclosed pastures with plenty of nice tall grass. In other words, these sheep produced long wool that we call long staple wool (A staple, in the context of textiles, is a cluster or lock of wool fibers). On the other hand, the older breeds of sheep that preferred more challenging environments produced short staple wool.

Woolen vs worsted

Woolen yarns contains lots of air, they're light, fluffy, and will often have small ends of fibre poking out of the yarn structure. They're incredibly elastic and bouncey.

Worsted yarns are smooth and dense, they tend to drape well and be much more lustrous.

Spinning machine invented by James Hargreaves in 1770.

The worsted wool gave the Guernsey its remarkable qualities: long, combed fibers created a smooth, dense, and water-repellent fabric. Knitted in the round on multiple needles, the garment was seamless, supple, and extraordinarily durable. Its reliability made it indispensable. Adopted by the Royal Navy as the “Guernsey frock,” it even reached the courts of royalty: Mary Queen of Scots is said to have owned Guernsey knitwear and wore Guernsey stockings at her execution.

The frock had its own entrance into Haute Couture, by the adaptation by Coco Chanel in 1917.

Portrait study of a sailor (wearing a frock underneath his jacket), Robert Williams, drawn by Philip James de Loutherbourg, 1740-1812

From these garments of endurance and utility evolved the next great expression in knitwear — the Aran sweater. The Guernsey’s practical geometry and maritime symbolism found new resonance on the Atlantic edge of Ireland, where the stitches themselves began to tell the stories of island life.

Aran Jumpers - A continuation of the Heritage

The origins of Aran sweaters are linked to the Congested Districts Board, a British organization founded in 1891 to combat poverty in western Ireland by teaching better fishing skills and knitting sweaters, to stop emigration from Ireland.

In the Aran Islands a knitwear industry was established which to this day provides Aran knitwear on a commercial basis using local skilled knitters and designers.

Fisherman of the Aran Islands wearing an authentic jumper

The Aran jumper transformed the fisherman’s uniform into a textile of meaning. While its structure remained practical — thick, insulating wool and close-fitting shape — some say that its surface became a canvas of symbolic stitches. Each pattern, repeated in endless variation, apparently carried a message, a wish, a fragment of heritage.

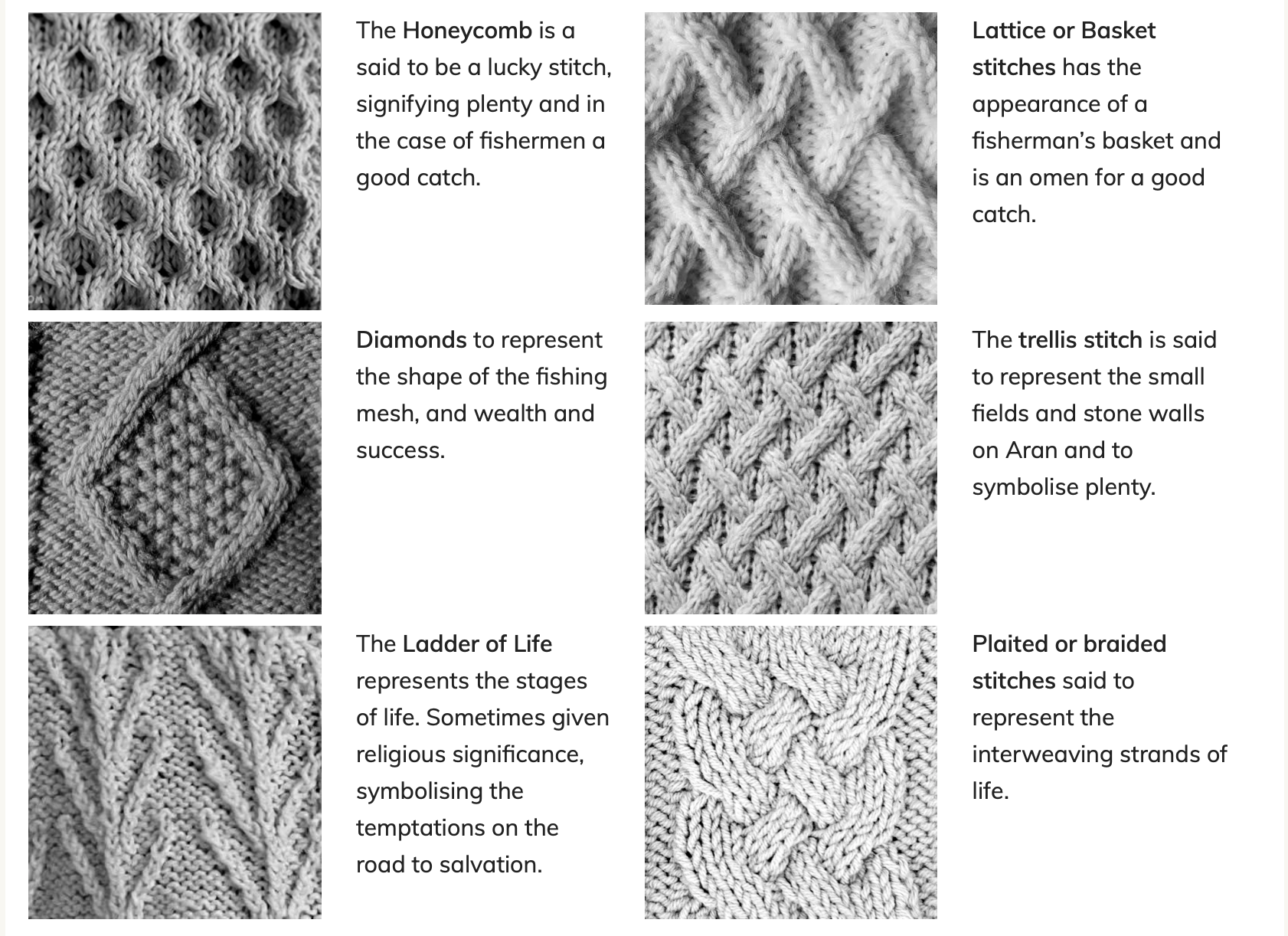

Aran stitches and their meanings - www.dochara.com

The truth is there aren’t really authentic meanings to any of the stitches, at least not ones that have any tradition or history behind them. Aran knitting is a relatively recent invention (most likely the stitches were created for their decorative appearance by clever and skillful knitters because they looked nice, not to convey any meaning.

The cable stitch, reminiscent of the fisherman’s rope, symbolized safety and good fortune at sea.

The diamond, echoing the fields enclosed by stone walls, represented prosperity and success.

The honeycomb stood for hard work and the sweetness of its reward.

The basket motif evoked hope for a fruitful catch.

These motifs were never merely decorative — they were language. Passed down from mother to daughter, they formed a silent continuity of memory and belonging. Each family developed its own distinctive arrangement, as if every household spoke its own dialect in wool.

Craft and Function: Wool, Wind and Warmth

The earliest Aran sweaters were knitted from local wool — báinín, unwashed and undyed, with the natural lanolin still present in the fibre. This made them warm, weather-resistant, and supple, alive with the irregularities of handwork and coarse island yarn.

By the 1930s, the Aran sweater had reached the mainland.

Muriel Gahan — The Woman Who Brought Aran to the World

Muriel Gahan

Every tradition needs a voice — someone who sees beauty in the ordinary and gives it a stage. For the Aran sweater, that voice belonged to Muriel Gahan (1897–1995): a visionary social reformer, artist, and champion of rural Irish crafts.

Born in County Donegal and raised amid the landscapes of Mayo, Gahan grew up with an eye for the quiet dignity of manual work. Her father was an engineer for the Congested Districts Board — the same organisation that would later shape the destiny of Aran knitting. From an early age she witnessed both hardship and resilience in Ireland’s western communities, and it left an imprint that guided her life.

‘Spining wool for Irish homespun’

In the 1930s, she founded The Country Shop in Dublin — a place where women from remote villages could sell their weaving, lace, and knitting directly to the city’s growing middle class. Later came the Irish Homespun Society and Irish Country Markets, cooperative initiatives that connected rural craftsmanship with fair, sustainable trade long before such words became fashionable.

Yet perhaps her most enduring contribution began with a single commission. In 1932, Muriel Gahan asked knitters from the Aran Islands to produce a sweater for an exhibition — the first adult Aran jumper ever recorded. From that moment, what had been a local knitting experiment became the symbol of Ireland’s craft identity.

Early Aran jumper of baínin wool - National Museum of Ireland

Gahan believed that tradition should never be fossilised but should evolve through skill, pride, and self-sufficiency. She organised workshops and training schemes, encouraging island women to refine their designs and adapt them to international sizing, so that Aran garments could be sold abroad without losing their authenticity. Her influence transformed the islands’ knitting into a viable livelihood — a bridge between heritage and modernity.

Beyond Aran, she tirelessly promoted Irish craft and education. She co-founded the Irish Arts Council, helped establish the weaving department at the National College of Art and Design, and served as the first female vice-president of the Royal Dublin Society. Her efforts culminated in An Grianán, a residential craft training centre in County Louth that still bears her imprint.

Muriel Gahan received numerous honours, yet her true legacy lies in every handmade piece that carries the warmth of Irish craftsmanship into the modern world. Without her vision, the Aran sweater might have remained a small island secret — instead, it became an icon.

Soon after, the English yarn company Patons published the first Aran patterns.

Aran Goes Global: Craft, Culture, and Fashion

During the 1950s and ’60s, the humble island knit evolved into an export phenomenon. P. A. Ó Síocháin, an energetic editor and social reformer, organised professional instructors — supported by a grant from the Congested Districts Board — to train local women to knit garments in standard international sizes. He even commissioned the Irish painter Seán Keating, who had spent years capturing island life on canvas, to design the marketing brochures. Knitting became not just a craft but a cornerstone of the island economy.

‘The Aran fisherman and his wive’ - Seán Keating, 1916

At the same time, Aran found its champions on the world stage. The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem, an Irish folk group recording in New York, adopted white Aran sweaters as their signature performance wear. When they appeared in 1961 on The Ed Sullivan Show — and later performed for President John F. Kennedy — their music and their sweaters together captured the imagination of the Irish diaspora. Orders for Aran jumpers poured in from around the world, and even with knitters recruited from beyond the islands, demand outstripped supply.

The Clancy Brothers & Tommy Makem - 1961

Fashion soon followed culture. In 1955, Dublin-born designer Digby Morton introduced Aran-inspired handknits at his London autumn show; by 1960, The Irish Times noted that the “Irish hand-knit look” was influencing Paris couture woollens.

Aran-inspired long cardigan by Digby Morton - 1960

The Language of the Stitches

The relief patterns of Aran knits still speak without words. Cables and braids echo ropes and nets, while diamonds and moss stitches create rhythm and balance. Technically, the twisted stitches trap air and retain warmth; visually, they form a landscape of light and shadow.

Around these motifs, countless legends arose — the cable as a symbol of safety, the diamond of fertility, the ladder stitch of life’s path. They are beautiful myths, yet mostly modern inventions. The German writer Heinz Edgar Kieweonce claimed that Aran patterns descended from Celtic religious symbols, but historians such as Alice Starmore and Richard Rutt have long shown otherwise. Still, these stories reveal how deeply people long to find meaning in the garments that keep them warm.

Into the World of Celebrity

The traditional guansey became increasingly popular, not least because celebrities such as Elvis Presley, Steve McQueen, Jane Birkin and Grace Kelly were photographed in it.

Elvis Presley, Jean Seberg and Steve Mcqueen wearing Aran jumpers

Prinses Grace wearing her Aran jumper - 1961

Decades later, in 2020, the Aran jumper resurfaced once more — worn by Taylor Swift in the photo shoot for her album Folklore, an image that circled the globe and reconnected the sweater with its romantic, storytelling soul.

The singer has a massive following on social media (nearly 137 million instagram followers) and the jumper sales boomed as a result.

Taylor Swift 2020

Studio Myr - Bridging Handcraft and High Fashion

In my work for Studio Myr, I seek to build a bridge between two worlds: the ancient art of hand knitting and the refined language of contemporary fashion. That is why Aran knits are so inspiring to me.

Every piece begins with a deep respect for those who came before — the women whose hands shaped warmth from raw wool, whose creativity and devotion turned necessity into beauty. Stitch by stitch, they wove protection against the elements, not only for themselves but for their families, carrying love, endurance, and skill through generations.

Their legacy is the heartbeat of my work. I see in their humble garments the same elegance, intention, and grace that define haute couture. What began as a fisherman’s protection has become a symbol of timeless style — proof that authenticity never fades, and that true beauty is born where craft meets soul.

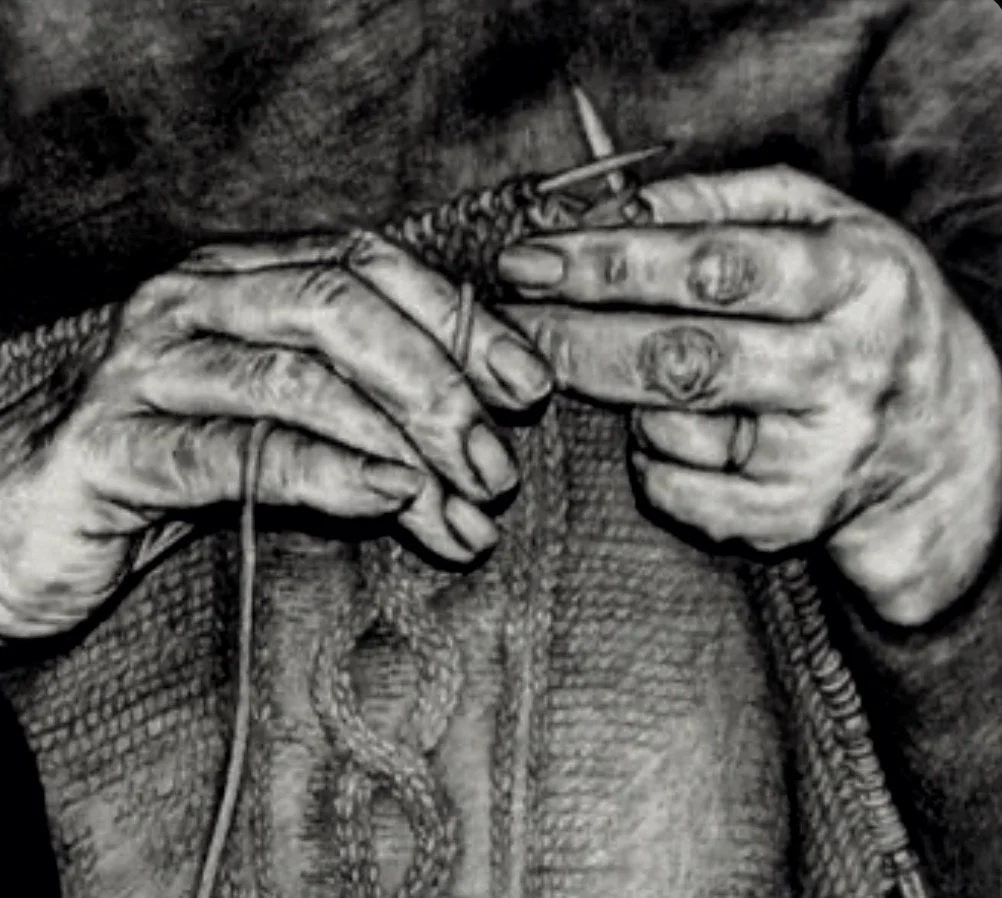

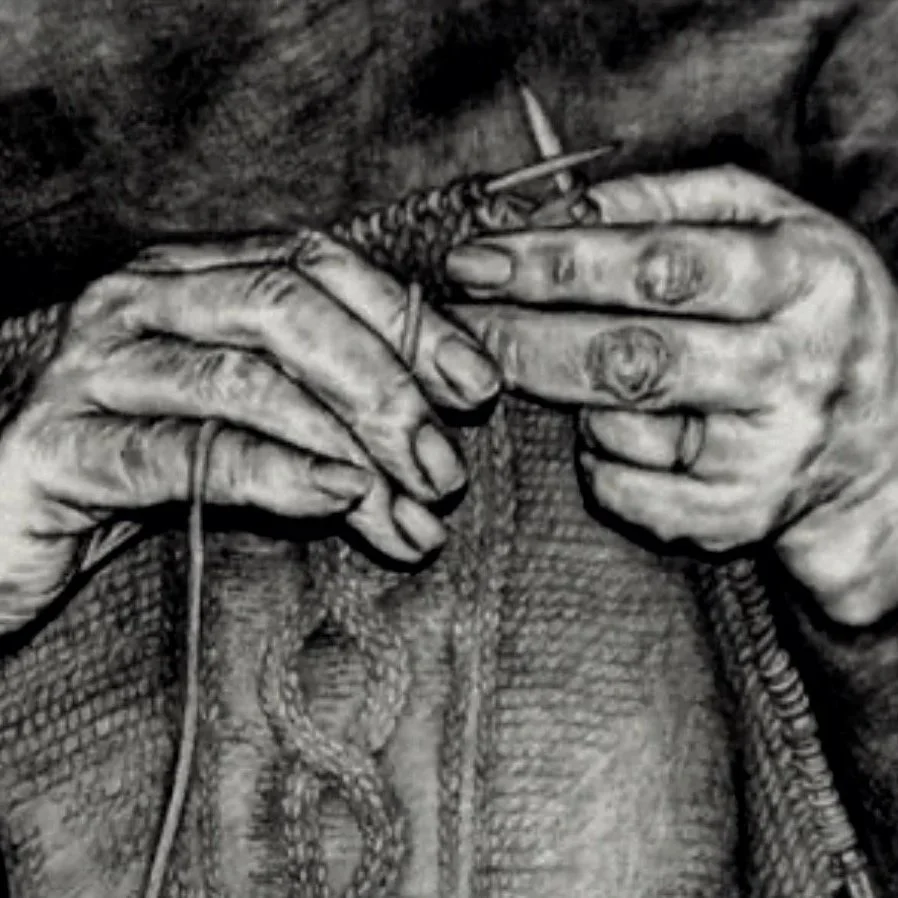

The first image — the working hands of a knitter — represents the roots of this tradition: strength, rhythm, patience.

The second — Prinses Grace of Monaco wrapped in the effortless sophistication of a cable-knit sweater — evokes the transformation of that same heritage into modern elegance.

Together, they form the dialogue that inspires every design at Studio Myr: a conversation between the past and the present, between handcraft and high fashion.

Studio Myr’s ARAN Collection

For Studio Myr, Aran is both heritage and inspiration — a language of texture, rhythm, and restraint. In my ARAN Collection, I’ve translated that tactile richness into contemporary silhouettes.

Aran headband and matching jumper Raven

The headbands and sweaters are produced locally in the Netherlands, in small runs, from a refined blend of extra-fine merino wool and mercerised Pima cotton. This combination gives the fabric a soft lustre and fluid drape while keeping the sculptural clarity of the relief.

Each piece — from the Fair to the Ginger and Raven headbands and sweaters — is hand-finished in my studio in Thorn. The colours are created by randomly blending multiple threads, producing a modern tweed effect reminiscent of the granite tones of the Galway coast.

Epilogue — The ARAN Sweater as a Story

In every stitch, I sense the rhythm of those women who once knitted on windswept islands — and of the Guernsey knitters along other shores who did the same: thread over thread, in silence, with care. What once shielded fishermen from rain and storm now celebrates craftsmanship, sustainability, and timeless beauty.

The Aran tradition reminds us that true luxury lies not in abundance but in attention. That warmth does not only come from wool but from hands. And that a sweater, however modern, can still carry a story — of sea, wind, and humanity.